Play allows us to access a state of “flow,” characterized by extreme focus, engagement, and sense of purpose

This page overviews a few simple, high-impact strategies for fostering creativity. Each comes from the classrooms of teacher advisers to the MCV initiative. These teachers have enabled the Museum team to spread these ideas to different age groups and contexts, gathering further documentation to explore and make visible the creative process. Through the process of spreading teacher practices, the MCV team has identified the ideas the resonated the most with other educators; some of these are below. Try them, tailor them, and share your experiences with the MCV team at mcv@cmaohio.org

What: Creativity Challenges are short, usually one-sentence prompts inviting imaginative action, often playful or containing unexpected juxtapositions (e.g. Design a feast for dragons). Creativity challenges are usually meant to be completed quickly (5 to 10 minutes)

Why: As a recurring routine, especially when coupled with regular reflection, creative challenges foster a culture of creative thinking and problem solving. They are quick, often fun and the whimsical nature of the prompts sets an unintimidating tone for engagement.

How: Begin with a collection of prompts (some can be found below) and open-ended, non-precious materials such as cardboard. Keep work time short to emphasize that this is to be a draft rather than a finished product.

click here for more on embedding, adapting, and expanding on creativity challenges

These tools are intended as “things you could try now” – with embedded suggestions for taking them further. We encourage you to test them out, to tailor them to your context, and to use them as springboards for imagining something new. We would love to see what you try, hear how you adapt them, and share your discoveries with other teachers.

Creativity Challenges Click to Download as pdf file

Creativity Challenges Click to Download as editable .doc file

One Challenge, Three Ways: Teams of elementary students, teens, and teachers tackle the same creativity challenge, with the same materials and parameters

***

The following resources were created by Core Teaching Team member Jason Blair. Jason designed these creativity challenges to connect with specific content areas and standards, but to be grounded first and foremost in thinking. While these challenges relate to grade levels, they can provide a model other challenges, projects and age groups.

Creativity Challenges Aligned with 2nd Grade Ohio Content Standards (click)

3rd Grade Creativity Challenges Tied to Ohio Content Standards (click)

5th Grade Creativity Challenges Tied to Ohio Content Standards (click)

Along with fostering play, purpose, and maker empowerment, creativity challenges can support new understandings toward curricular standards

Art teacher Laura Koontz elaborated on a basic challenge format by giving groups an egg carton, a couple of open-ended materials, and two randomly selected verbs (from a list created by the artist Richard Serra.) The student quote, which Ms. Koontz juxtaposed with the group’s creation, speaks to some of the connections and thinking the experience prompted.

What: “Things to try” mini-posters capture some simple ways we have seen teachers support creative thinking

Why: Each idea comes from a classroom we observed through MCV, and each is coupled with either a statement about the kind of thinking it provokes, or a reflection question to extend your thinking.

How: Post near your desk, where you plan, or anywhere you want inspiration for a zero-prep spark for creativity and reflection.

What: Creativity – What’s the big idea poster communicating CMA’s definition of creativity and some key ideas about its importance

Why: Even as more and more experts are clamoring for creativity in learning, much advocacy remains to be done. This poster makes visible some “whys” behind creativity, so that students, colleagues, administrators, families – anyone who enters your classroom can be reminded that creativity isn’t an extra. Creativity is fundamental.

How: Post it in your classroom, teachers’ lounge, conference room – anywhere people can benefit from these messages.

What: ODIP – Observe, Describe, Interpret, Prove critical thinking routine for looking at anything

Why: Careful noticing is a foundation of critical thinking. People have a strong impulse to jump to immediate, knee-jerk reactions before considering evidence and multiple perspectives. This tendency inhibits empathy by confining us to our own limited perspectives, shuts down respectful debate, and leads us to make false interpretations. The ODIP process helps users of all ages slow down, closely observe, resist initial assumptions, develop theories based on multiple points of evidence, and justify interpretations. These habits are foundations of depth, complexity, empathy, and fresh thinking in any field.

How: To use this critical thinking protocol, you will need an object students are likely unfamiliar with – a work of art, a poem, a historical document, a scientific photograph, an item from nature, or anything that might pique student curiosity. It is important to withhold any identifying information about the object until students have had ample time to investigate using the protocol. Facts or expert interpretations limit student curiosity and interest in “figuring out.” This graphic can be printed out and posted in the room, or download this one-page guide that walks you through the protocol: Educator’s guide to looking at anything

What: CMA’s What if? poster featuring a work by the artist Kehinde Wiley

Why: Imagining things as if they could be otherwise, and calling attention to what is often unnoticed are important ways that artists help us think differently.

How: The physical environment of the classroom teaches students all the time by communicating values. Post this on your door or another visible spot to enforce the importance of “what if” thinking.

What: What Makes You Say That? Tell Me More.

Why: Open-ended prompts support students to probe their own thinking, and allow educators to gain a greater understanding of the perspectives of the person we are speaking to.

How: These simple prompts should be a staple of conversation in the classroom and beyond. Use them to prompt elaboration and clarification.

What: Think Puzzle Explore Thinking routine from Harvard’s Project Zero

Why: This routine prompts students to surface what they think they know about a subject, builds their curiosity, and sets them on a path of exploratory engagement – thinking habits that are foundational to creativity.

How: Ask students 1) What do you think you know about this topic?, 2) What questions or puzzles do you have? 3) What does the topic make you want to explore? This can be done individually, or as a group. Making it visible to the group and referring back to it can help students chart the evolution of their understanding and curiosity.

Ms. Risner’s fourth grade students began a unit on the Earth by doing Think Puzzle Explore; the result is posted for the group to revisit over the course of a unit. Students write additional “wonderings” on the adjacent white board.

Students record their “wonderings”

For further Project Zero thinking routines, visit http://www.pz.harvard.edu/search/resources

What: 21 Days to More Creative Thinkers is a guide to using improv to foster creativity in the classroom.

Why: Similar to creativity challenges, improv activities support various habits of idea generation, and support a culture of adventurous, divergent thinking. Elementary teacher Patrick Callicotte embraced the way improv theater in the classroom fundamentally rejects failure, and sets the expectation of flexibility. Mr. Callicotte designed this tool to tap into the popularity of the “21 day challenges.” While the experiences do not need to be completed in order, the challenge design supports the user in making improv routine (rather than one-off). This, in turn, supports the development of a culture of creativity.

How: Color-coding distinguishes 3 minute warm-ups, 10-minute exercises, and 30-minute activities. Use a QR reader (free and downloadable from an app store) to open directions and examples from Mr. Callicotte’s classroom. Start by getting yourselves and the students into a playful, silly mood. Mr. Callicotte begins with a “follow the leader”-style warm-up in which students exactly mimic him while he makes absurd movements and sounds.

QR codes link to directions and examples of dynamic experiences to spark creativity

Download the tri-fold, two-sided 21 Days of Improv pdf

What: Design for curiosity

Why: Imaginations are stretched when they encounter new or unexpected things. The physical environment is a powerful force that impacts learning – for the good or for the bad. Whether a small tweak or a big remodel, being intentional about the way the classroom space supports creativity is profound. Adults and peers can play a role in feeding the group’s imaginations, as the examples below illustrate.

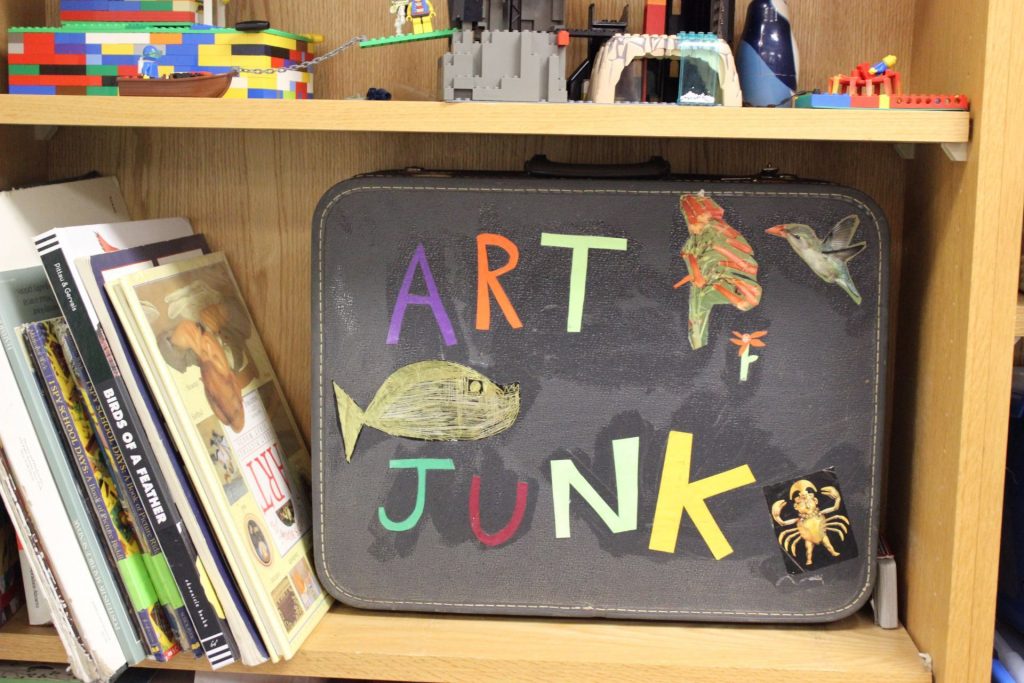

How: Create a physical space in your learning environment that specifically seeks to foster curiosity. This could be a shelf that houses a collection of items that spark wonder, a wall where students can post things that intrigue them, or a portable collection of interesting junk.

Students add a huge range of objects that capture their attention – Ms. Reiser’s only rule is that it can’t mold.

When artist and high school teacher Todd Elkin (Alameda County, CA) visited an art museum with his high school students, he realized that art works didn’t speak to his students the same way they spoke to him. He realized that he needed to make space for students to share what “grabs” them. Thus was born the “grab wall” – a dedicated space for students to showcase things that grab them. This particular “grab wall” (in Emily Reiser’s elementary art room) presents photos of a neighborhood albino squirrel, a sheet of paper that was removed from a jammed shredder, a lollipop whose wrapper resembles a superhero cape, and myriad other things students found captivating. Creating such a space validates close observation and curiosity, both building blocks of creative, critical, and empathetic thinking.

The “Art Junk” box houses all-purpose, open-ended inspiration

Emily Reiser’s Art Junk suitcase was born when she came upon a vintage suitcase in the garbage. She filled it with other objects destined for a landfill, such as broken toy parts and oddly-shaped implements, with the intention of using them as models for drawing lessons. However, the simple resource with its strange objects became hugely popular among students. When students are stuck on any sort of project, they often visit the Art Junk suitcase for inspiration. Even if they do not directly “use” any of the objects in their work, simply walking away from a project and exploring strange things can be enough to help a learner get “un-stuck.” This tool may be particularly attractive for teachers who do not have a dedicated classroom space.

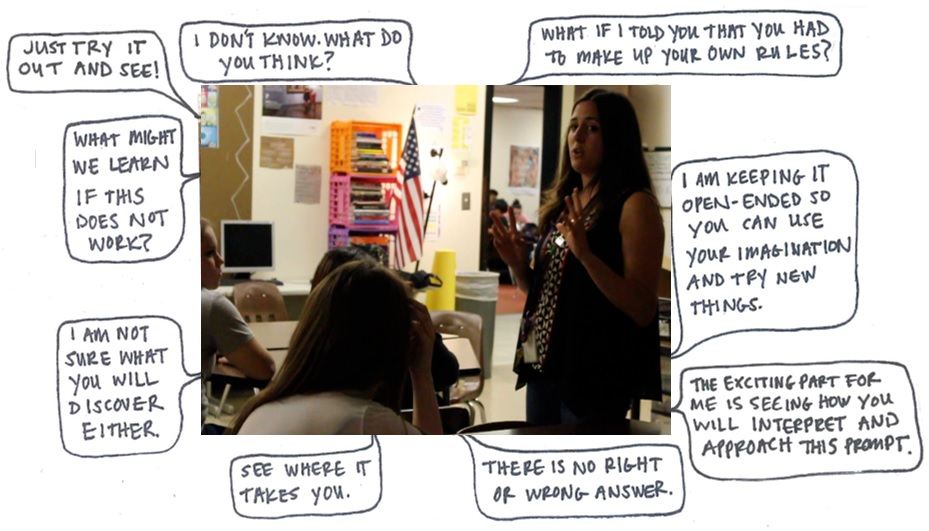

What: Use the language of creativity The What might creativity sound like? tool was developed in collaboration with teacher advisers of MCV and of CMA’s Leaders for Creativity fellowship program. Teachers were asked what language supports or indicates each habit of creativity on the Thinking Like an Artist rubric. Their responses were so rich that The language was so rich that MCV documenter Maddie Armitage created this tool, which uses speech bubbles to make this language visible.

Why: Language plays such an enormous role in the culture of learning environments. Most of what happens in classrooms is mediated through language. Being intentional about language allows us to harness its power. If we are not intentional about the language we use (or don’t use), we are missing opportunities, and indeed may be undermining our own efforts to teach for creativity.

How: Post this document in a common staff area, or your classroom. Look through the “language moves” and challenge yourself to integrate one or two from each page into your vocabulary. Use the phrases in ways that feel natural, but do so routinely. Over time, notice if students and/or colleagues adopt the phrases you have integrated.

Teachers shared what it could sound like to foster different dispositions of creativity, in this case “tolerance for ambiguity”

What Might Creativity Sound Like? (click to download pdf)