Experts across sectors are increasingly emphasizing the need for creativity. Creativity is identified as a key aspect of the future of work, a lynchpin of global competence, an important aspect of empathy, the basis of innovation, and a necessary ingredient to personal fulfillment. But what is creativity? What assumptions about creativity hold us back from nurturing it for ourselves and others? What habits characterize creative thinking, and what do they look like in learning?

The Columbus Museum of Art defines creativity as “the process of using imagination and critical thinking to generate new ideas that have value.” In other words, creativity involves seeing things as if they could be different, or envisioning things that do not yet exist. It also involves using analytical thinking to assume different perspectives, evaluate options, refine, and then bring a new idea into the world in some way. Creativity is deeply linked to empowerment, empathy, and fulfillment. Creativity is the basis of innovation in ways both large and small.

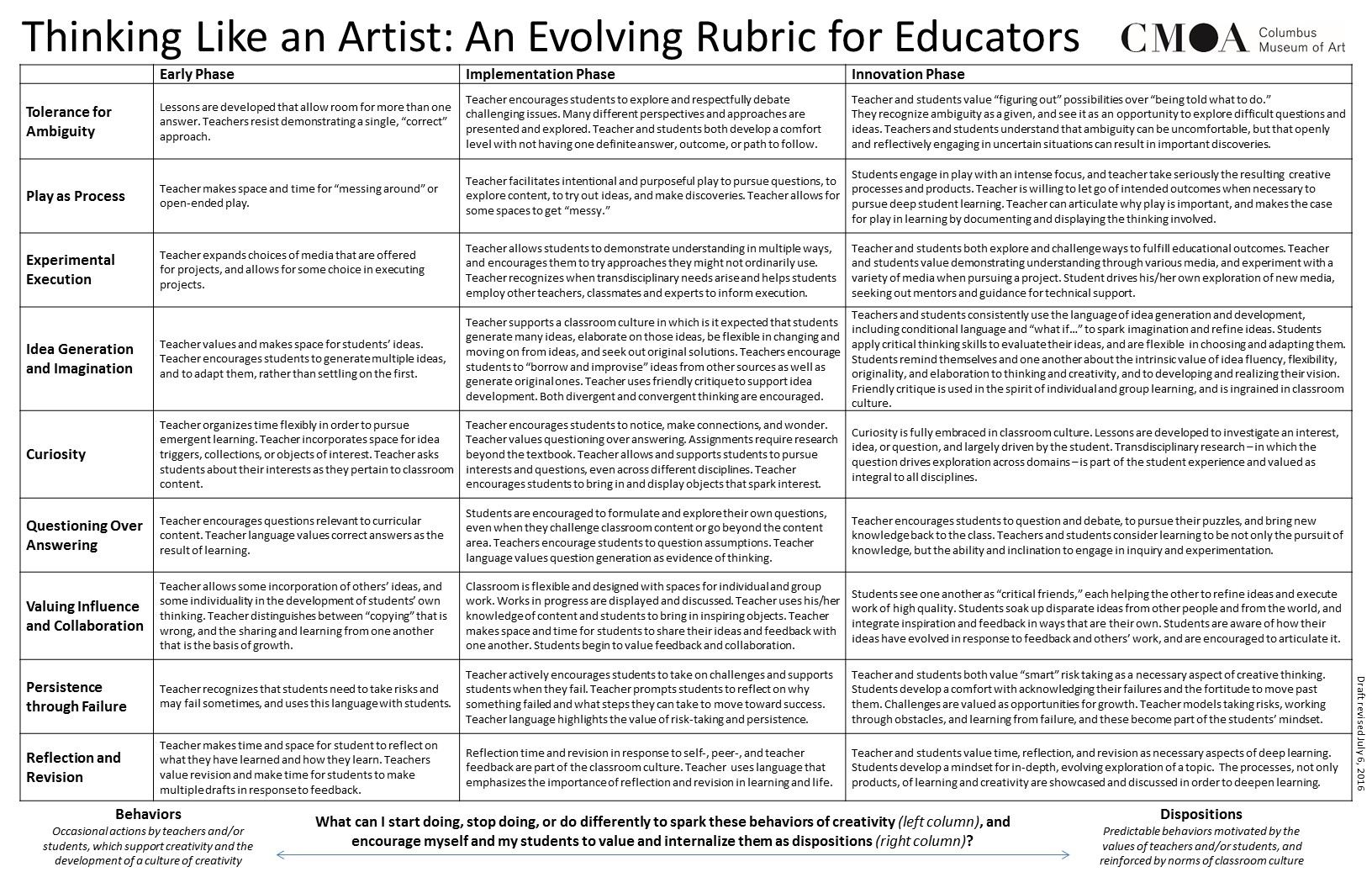

Looking to artists as models of creative thinking, the CMA has created the evolving Thinking Like an Artist framework. This framework results from many years of research in learning environments, through literature on creativity and artistic practice, and in conversation with practicing artists. This research is ongoing (reflecting the learning inclination of the CMA) and the framework is evolving.

This framework is the basis of the evolving. Thinking Like an Artist rubric:

The Thinking Like an Artist framework currently comprises the dispositions below; each disposition is followed by a description. Note that these dispositions interact with one another, and as with any type learning, they look different for different people.

Tolerance for Ambiguity

Tolerating ambiguity means being able to engage in the uncertainty that permeates all aspects of life and work. The need for clear directions inhibits our originality and limits our comfort zone to those ideas that are easily explained and those paths that have already been mapped. To be successful personally and professionally, we must be able to navigate uncertainty, eagerly take on new challenges, develop independence, and create new understandings.

Kicking off a year-long exploration by embodying uncertainty and embracing vulnerability

In classrooms characterized by high tolerance for ambiguity, teachers and students value “figuring out” possibilities over “being told what to do.” Ambiguity is recognized as a given, and seen as an opportunity to explore difficult questions and ideas. Teachers and students understand that ambiguity can be uncomfortable, but that by openly and reflectively engaging in uncertain situations we can come to important discoveries.

Play as Process

Play is done for its own sake and propels itself forward because we enjoy it. It gives us access to serendipity and unexpected discoveries. Open ended play has genuine value as its own pursuit; the fields of neuroscience and human development indicate that play is learning.

TASK Party is a participatory experience designed by the artist Oliver Herring. Here, teachers at CMA’s Teaching for Creativity Institute take on ambiguous tasks, and devise their own for others to interpret. Here, CMA interspersed a special “task” – to use pre-printed speech bubbles to interview participants about their process (bottom right). MCV educators have used TASK party in classrooms of all types; for more on TASK, see the Other Resources page.

In a classroom characterized by creative play, seemingly purposeless exploration of ideas and materials is valued as a way of thinking. Teachers document students learning through play, and make clear the thinking involved. Teachers and students mess around with a variety of media to advance learning, explore content, and make discoveries in ways that are self-directed and teacher-supported. The unexpected is encouraged and made visible by teachers and students.

Experimental Execution

Experimentation is the way that we test out our hunches, better understand the known and the unknown, and introduce ourselves to the unexpected.

Trying out different ways to construct a light fixture to “illuminate” a social issue

In a classroom characterized by experimentation, teachers and students embrace and encourage “figuring it out” over “looking it up,” and trying many paths over settling on the first. Experimentation is a transparent aspect of instruction, with teachers modeling the ways they are trying out ideas and approaches. Teachers and students pursue their curiosities, test out, and examine. Divergence and novelty characterize the processes and products of teaching and learning.

Idea Generation and Imagination

Imagination is the ability to see what isn’t there, or to see things in new ways. Imagination fuels our ability to generate many ideas (fluency), adapt ideas and conventions (flexibility), and build on and extend others’ ideas (elaboration). Imagination, fluency, flexibility, and elaboration, help us solve problems, generate questions, and create ideas that matter to us and/or others. Originality follows from these habits; as we come up with many ideas, twist, refine, and build on them we are more likely to arrive at something new.

Teachers at the CMA’s Teaching for Creativity Institute collaborating on a creativity challenge

In a classroom characterized by imagination and idea generation, teachers and students use conditional and “what if” language to fuel their brainstorming, and open-ended “What makes you say that” and “Tell me more” type language to extend thinking. Imagination is intentionally fueled by bringing in objects and collections that spark wonder. Time and space is made to generate many ideas, build on them, adapt them, and make them original.

Curiosity

Curiosity is about what we wonder – how we look to, engage with, and explore what is around us. In personal and professional life, curiosity is inherently transdisciplinary – we wonder and develop questions that drive us across arbitrary boundaries of what we call “disciplines.” Curiosity is the beginning of everything we will ever know, think, or wonder.

By carefully observing elements of this art work, “Americana,” students became increasingly curious about and engaged with the complexities of U.S. national identity

In classrooms characterized by curiosity, time and space is made to discuss what students wonder about. Noticing and questioning are encouraged in and out of class projects. Student interests and questions are taken seriously and pursued, even when they seem unusual or outside of the conventional parameters of the classroom content.

Questioning Over Answering

New understandings and approaches come about by developing, refining, and exploring questions. Questions are how we engage with the unknown, and how we apply what we know to new discoveries and pursuits. Questioning is an entry point for exploration, a foundation for understanding, and a building block of empathy.

High school students creating mind-maps to raise questions about learning environments as an initial research step for piece of “graffiti-style” art

In classrooms characterized by questioning over answering, learning is not framed as content mastery, but investigation of the unknown. Valuing questioning over answering means shaping classrooms around the belief that it is complex questions, not easily-assessed answers, which drive learning. Teachers engage in inquiry and experimentation, approach their role as a curious learner, and make that visible and transparent to students.

Valuing Influence and Collaboration

No thinking happens in a vacuum, and the best ideas emerge when we intentionally and responsively harness collaboration. Innovative and imaginative thinkers in all realms have a voracious appetite for what is happening around them, what has come before, and the feedback and collaboration of others. When individuals are supported in both seeking out the contributions and expertise of others, and in contributing in meaningful ways to others’ thinking, cultures of creativity thrive.

Collaborating to design a city for an imaginary creature, based on information gathered by the whole class

In classrooms characterized by collaboration and influence, the influence of multiple creative actors is made visible to students; in other words, students are encouraged to see the ways in with the contributions of others helped shape “their own” work, and how they contributed to the ideas of others. Students see one another as “critical friends,” each helping the other to refine ideas and execute work of high quality. Students soak up and seek out disparate ideas from other people and from the world, and integrate inspiration and feedback in ways that are their own. Students are encouraged to recognize how ideas are the result of collaboration, and to see themselves as participants with unique and wide ranging contributions to generating and executing ideas with value.

Persistence through Failure

Smart risk-taking is a necessary aspect of creativity; only when we challenge ourselves and try something new will we come to new discoveries. In turn, taking on new challenges increases the likelihood of failure. Struggle and failure advance our creativity when we learn from them, push through, and emerge encouraged to keep trying new things.

A few criteria must be considered in order for failure to be constructive. Firstly, the risk should be intentional and linked to something the learner values or wants to achieve. Sloppy mistakes might yield lessons, but not breakthroughs. Secondly, learners need to have the time, routines, and sense of support to push through and learn from failures. Finally, educators have a responsibility to recognize that what is a legitimately risky act for one person might be trivial for another. Emphasizing “risk-taking” and associated notions with creativity can lead us to recognize creativity in certain acts that are more easily taken by individuals with safety nets. A common example of this is stories of people who eschew college and career to launch a start-up. Conscious educators will recognize creative risk-taking in the context of the individual learner’s goals and experiences. Trying new challenges enables us to learn, grow, and affect change. This disposition seeks to recognize the importance of being willing to try new challenges and learn from mistakes.

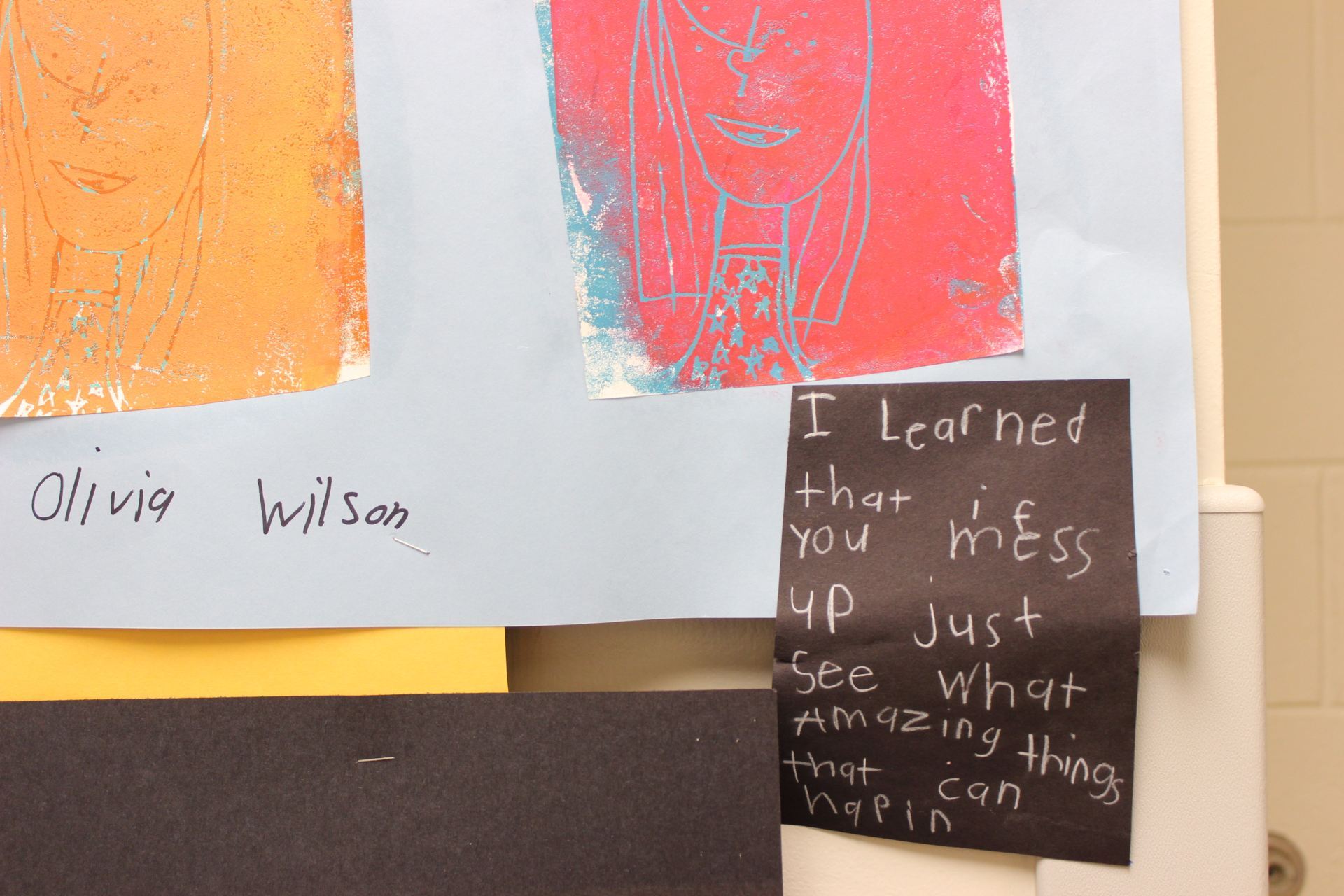

When asked what she wanted to share with visitors to the school art show, this student reflected on what she learned about mistakes

In classrooms characterized by persistence through failure, teachers and students value tackling new challenges as a necessary aspect of creative thinking. Drafts and iteration are the valued expectation. Students develop a comfort with acknowledging growth areas and an inclination to learn from mistakes. Challenges are valued as opportunities for growth. Teachers model their own failures and ways they work through obstacles, and what they learn through failure.

Reflection and Revision

Reflection allows for the comparison, analysis, and critical assessment of different ideas, possibilities, and drafts. Imagination allows us to come up with many ideas, think flexibly about objects and ideas, extend and expand, and originate novel ideas. Reflection and revision allow us to critically regard divergent ideas, and to converge thoughtfully on a path forward, be it a next step in bringing an idea to life, a revision on a draft, or a change in approach. Moreover, reflection during and after the creative process leads to deeper thinking, higher quality feedback for one’s self and others, improved metacognition, and long-term creative and critical growth.

Reflect on group discussions exploring social issues in order to develop an idea for a project

In classrooms characterized by reflection and revision, the learning process is documented in different ways and shared with the learners. Time for regular reflection and revision is prioritized. Open-ended processing time as well as structured feedback protocols are used to support self-assessment and constructive peer critique. Students and teachers value making multiple drafts and highlighting the evolution of ideas. The processes, not only the products, of creativity are showcased and discussed in order to deepen learning.